Fall may seem like a strange time to be thinking about fly control, but it is the perfect time to review what you did this summer and start planning for next year!

Developing an integrated fly control program is essential to reduce loss not only next year but for years to come.

Knowing which kind of fly you are dealing with is the first step in developing your program.

There are three major flies which cause loss in pastured cattle: horn, stable and face flies.

Horn flies are small flies seen on the back and bellies of cattle with the fly head facing downward (Figure1).

Cattle under fly pressure will often toss their heads back trying to disturb the flies, tail swish, bunch together and bump up against each other in an effort to give their flies to their herd mates.

Stable flies are larger and prefer to feed on the legs with their head facing up towards the sky (Figure 2).

Fly worry signs include leg stamping, belly kicking, tail swishing and animals bunching together showing general agitation.

Cattle can sometimes be seen bunched up against a fence line or standing in ponds to try and escape painful bites.

Face flies are often found around the eyes, nose and mouth and transmit the pathogens which cause pinkeye.

Animals may show general agitation and head shaking (Figure 3).

Fly control is not a ‘one size fits all’; these flies have different habits and breeding sites and you need to target your fly control approach to each species.

Watching your animals for fly worry behaviors and observing areas flies are found should be used to determine which flies you have and build on your control approach.

The most impactful fly control intervention for population reduction will always be removing breeding sites.

Each female fly will lay several hundred eggs during her lifetime. Horn and face flies will only lay eggs in fresh intact manure.

Maggots need to be within the manure pat to survive and will only leave the manure when ready to pupate and become adults.

Dung beetles (Figure 4) are the unsung heroes of grasslands, removing and burying manure which not only removes the breeding site for flies but also for gastrointestinal nematodes.

Dung beetles reduce pasture fouling, improve soil aeration and nutrient cycling and are very susceptible to macrocyclic lactones so avoid using injectable and pour-on avermectins (abamectin, eprinomectin, ivermectin, etc.) during spring, summer and early fall.

Due to their faster elimination times, white wormers (benzimidazoles) may be less damaging to dung beetles, but their negative impacts have not been established in the native dung beetle species we need.

A feedthrough insect growth regulator (IGR) blocks the ability of flies to develop within the manure pat.

To be effective, each animal must consume the correct amount; however, cattle consumption of free choice mineral varies significantly.

This causes some individuals to eat either too much or too little with too little being the major concern.

Underdosing leads to accelerated development of resistance resulting in reduced efficacy over time.

There is a common misconception that insects cannot become resistant to IGRs, which has been shown in multiple studies to be untrue.

If you do use a feedthrough IGR, rotate annually between a methoprene (e.g., Altosid) and diflubenzuron (e.g., Clarifly, Justifly) based product to slow the rate of insecticide resistance developing.

While garlic has received a lot of attention in recent years, controlled trials have shown no difference in fly burdens between cattle which are given garlic and those who are not.

In contrast to horn and face flies which breed in fresh manure, stable flies will happily breed in any wet and decaying plant matter, especially if contaminated with animal waste.

Large round hay bales are a primary breeding site for stable flies so reduce hay waste by feeding high quality hay and spread waste to dry it out, thereby killing maggots and removing the breeding habitat.

Removing flies from animals reduces fly worry and economic loss as well as reducing the overall population.

Horn flies stay on their chosen animal 24/7 and will die within a few hours of being off the host.

This makes on-animal control options more effective than for stable or face flies which are only on the animal for a few minutes, spending the rest of their time sheltering in vegetation.

The Bruce’s walk-through trap can be very effective for horn fly control if animals pass through it regularly (https://www.iowabeefcenter.org/bch/ HornFlyTraps.pdf).

These are also effective against other fly species including stable flies, face flies and tabanids (deer and horse flies).

The more often cattle walk through, the more flies are removed so placing them on the way to water or feed is most impactful.

Adult animals can carry lower horn fly burdens (approximately 300 flies) without any negative impacts and any chemical control options should only be used once flies go above this level (Figure 5).

Insecticides come in many formulations and application methods.

With so many options, it is often easier to just stick with what has been used year after year.

Unfortunately, this approach drives insecticide resistance, limiting your choices in the long run.

Insecticides should be used sparingly and only as part of a larger integrated pest management program.

Ear tags offer a convenient method for horn and face fly control, as well as some ear associated ticks.

Tags are available in all three major chemical groups (pyrethroid, organophosphate and macrocyclic lactone).

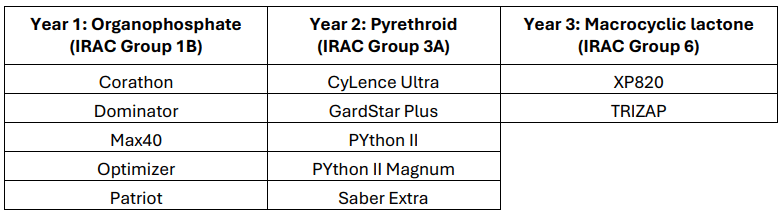

You should rotate chemical class annually; Table 1 gives some options for each group. In field trials, tags offer approximately 100 days of horn fly reduction compared to untagged cattle.

The mistake people often make is to put tags in too early as cattle go out onto pasture in the spring.

The tag’s most effective time period is effectively being used up while fly numbers are relatively low.

Although it may be less convenient, delaying tagging by a month or two will give you protection over the peak fly period.

While adult animals can maintain lower fly burdens without loss, weaned calves are less tolerant to parasitism.

Tagging stocker calves before going onto pasture will significantly improve average daily gain.

To get the most bang for your buck, follow good tagging practices. Insecticide ear tags work by coming into contact with the skin surface.

Insecticide transfers from the tag to the skin and spreads through the natural coat oils.

Tagging only one ear is a common practice but only half the body is protected if you use this approach.

This is particularly important when using tags for face fly control. Tag cows and weaned calves but not calves still on the mother.

Tagging bulls is also not recommended because they do not have the neck mobility to make tagging effective.

Do not daisy chain tags because it does not give enough contact to be effective.

Remove tags when they lose efficacy or at the end of season and do not retag cattle within the same season.

A pour-on can be used for horn fly control and should be used in the same rotation as ear tags.

Bear in mind that macrocyclic lactone pour-on will impact your dung beetle populations.

If you do not want to use macrocyclic lactone products, use organophosphate chemicals for two years followed by one year of pyrethroid chemicals in a 2-1-2-1 rotation.

If using multiple application methods together, make sure you synchronize chemical class.

For example, if you use a self-applicator to treat animals in pasture with an occasional spray, make sure that both chemicals fall in the same group.

For example, if you have Prozap in your back rubber, the active ingredient is permethrin which is a pyrethroid (IRAC group 3A).

Make sure you pair it with a pyrethroid spray such as Permectrin II or Permethrin 10 rather than Co-Ral which is an organophosphate so that all chemicals for that year fall into the IRAC group 3A.

If using an organophosphate like Prolate/Lintox-HD in a back rubber, you can also use it as a spray, Co-Ral or any another organophosphate (IRAC code 1B) based spray.

The Vet Pest X website is a searchable database which can help you make insecticide product selections (https://www.veterinaryentomology. org/vetpestx).

Injectable macrocyclic lactones have become popular due to their convenience and longer coverage length.

Due to the long elimination times, they will select strongly for insecticide resistance and should not be used for insect control.

Pasture management can be used to supplement your fly control practices.

In areas where burning is permitted, pasture burning in the early spring can be used to reduce both fly and tick populations.

Horn flies are capable fliers with estimated flight range of 3-10 miles. Pasture rotation can be effective especially the further away cattle are moved.

Even if you cannot move cattle far distances, making the newly emerged adult flies move even a little further to reach cattle after emerging can reduce chances of the fly reaching a host.

In conclusion, watch cattle to identify which fly species you have and then build your program to target both larval and adult flies.

Rotate chemical class to slow the spread of resistance and always use according to the dosage guidelines. Store unused chemicals in a cool dry place out of the elements to preserve their shelf life.

Note: All references to commercial products or trade names are made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by K-State Research & Extension is implied.

Dr. Cassandra Olds serves as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Entomology at Kansas State University where she has a 50% Research, 30% Teaching and 20% Extension appointment. She received her PhD from the University of Basel in 2012 and underwent postdoctoral training at Washington State University and University of Idaho. She serves as the Veterinary Entomology Extension specialist for Kansas but also provides services to other states. Her research and Extension program are integrated to tackle producer’s insect and tick problems. She works closely with producers and veterinarians to evaluate the impact of arthropod pests directly in the field with the goal of developing sustainable pest control strategies to mitigate economic losses.

Dr. Cassandra Olds serves as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Entomology at Kansas State University where she has a 50% Research, 30% Teaching and 20% Extension appointment. She received her PhD from the University of Basel in 2012 and underwent postdoctoral training at Washington State University and University of Idaho. She serves as the Veterinary Entomology Extension specialist for Kansas but also provides services to other states. Her research and Extension program are integrated to tackle producer’s insect and tick problems. She works closely with producers and veterinarians to evaluate the impact of arthropod pests directly in the field with the goal of developing sustainable pest control strategies to mitigate economic losses.

Get all Doc Talk episodes straight to your email inbox!